Writer Lourdes Walsh shares her initial skepticism about #flexappeal

My first impression of Flex Appeal – a kaleidoscopic bombardment of lycra-clad women on my social media feeds – was not the most positive. A bunch of middle class, mostly white women with the privilege of career. Most, if not all, seemed to be living in their own homes, or at least with home security.

We are not of the same tribe.

They wanted to be able to collect their kids from school two afternoons a week, I wanted to be able to feed my kid two afternoons a week.

Calling for flexible working is all well and good. It’s a cause primarily benefiting women, as we are still the majority care-givers within every society. As a feminist, I’m all for that.

And yet, flexible working seemed to serve only a very small demographic of working women; the educated, those with five-year plans, life goals and a voice of agency.

I have been in employment for my child’s entire life. I was self-employed through my pregnancy and went back to work when he was six weeks old, having graduated from art school at 37 weeks pregnant. As a single parent I was never judged or berated for this. If anything, I was pressured to return. Single parents are demonised and I felt the constant need to prove my worth. That meant paying my way.

As a single parent, self-employment was not working. I needed stability and financial guarantees. I needed to pay London rent amid a housing crisis. As a single parent you are often pigeon-holed a ‘scrounger’. We are to work in anything, accept everything, no matter the detriment. I was a roach sifting through the scraps of job listings.

I said yes to whatever I could. I worked shifts in a pub, my colleagues taking turns to build Lego with my son at a corner table hidden from the boozer’s patrons. I was fortunate enough to have a manager who listened when I said I HAVE to work a certain number of hours. Inevitably though, I couldn’t have all the day shifts. Others had responsibilities too: relationships, auditions, degrees and second jobs.

I created a WhatsApp group among friends to farm my kid out when I worked late shifts. With one friend, I would drop my son off to at 5pm, then collect him after midnight, pulling him from the warm nest he shared with her own son, carrying him over my shoulder home in his pyjamas and out through the cold.

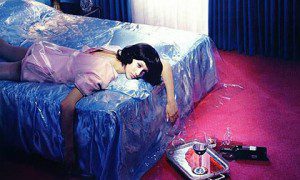

It leaves a constant pit in your stomach, a piercing headache of logistics. There’s hair loss and acne, there’s weight fluctuations and bouts of insomnia. Stress. Anxiety. Fatigue.

It’s relentless.

I did find another job, though. A job I was over-qualified for and passionate about. It was a rung on the ‘career ladder’. I felt inspired and hopeful and for the first time in too long I could let my shoulders drop and take a breath. I was working for London’s leading children’s theatre and from the very beginning I was honest about my ‘situation’ – that I have sole physical, emotional and financial responsibility for a child.

My working pattern was flexible, a few 9am starts and 4pm finishes. I hesitate to call it the dream – a working life that works with the needs of, you know, life – but initially it worked. Before long this was stretched: 4pm finishes became later, then a Saturday afternoon, then every Sunday morning. And then, suddenly, a change: everyone who had started within the last six months was put on a zero-hour contract.

Zero-hour contracts are the Wild West of the job market. Your boss is under no obligation to give you any work. People are ‘in work’, but no shifts means no money. Often people are only informed days before their shift, sometimes the morning of it. The number of single parents having to take on zero-hours has increased exponentially in the last decade. A recent study confirmed an increase of 58% in which single parents entered zero hour contracts and precarious self-employment status.

For women like me, this means paying for childcare you may not use. That’s bad business in anyone’s eyes and bad business leads to debt, sped along by the complexities of claiming tax credits or housing benefits, and the spiral into poverty is swift and devastating.

My ‘employment’ meant I was no longer entitled to housing benefit. But my contract meant I had no guarantee of work. I had no money coming in and I was still haemorrhaging cash for childcare and heat and food.

Within a month I was in arrears that it has taken me years to clear.

Working life doesn’t always work. And when it does, it doesn’t work well enough.

My current employment status is marginally better. I am forced into any entry-level job, a minimum wage, no progression. I work long hours, alone, without a break. I have too much to lose if I speak up, never mind suggest flexible working. Never was my lack of autonomy more evident than this summer.

I had spoken to my manager about needing to leave early, change days, make allowances for summer holidays, always aware of my desperate need to stay contracted. I end up retreating, appeasing the boss to the detriment of my family.

When you work into the evening and all the childcare clubs finish at 6pm, there have been more days than I should admit to that my child has sat cramped and confined in a back office with nothing but Horrible Histories for company.

This summer I was reported for bringing my kid to work. By another woman: one with the power of flexible working and no child, working in head office. The news was ‘cascaded’ to me: “Don’t bring your kid to work.”

School starts back, with the 3.15pm finishes and the four hours of childcare to cover. After-school club is over-subscribed, childminders are already catering to those who can pay more. And so we’re back to the scrappy ‘who can?’ negotiations, payment in kind, too often indebted to the flexible workers in the playground.

Single parents are left out of every decision-making process in society, so of course they would be left out of the debate on flexible working. I wasn’t invited by a manager into an office to discuss anything. There was nowhere I could go to explain my situation in a way that dignified me as a human, as a parent, as a capable adult.

But it got me thinking. If people without children can work flexibly, then why can’t I?

I’ve said Flex Appeal – the initial conversation – wasn’t mine. I stand by that. But this Flex Appeal call is different. If all women are invited to the table, all working patterns and all salary status’, it can, it will, open the doors for everyone. We’ve said it’s not our fight, and they listened, questioned and listened again. It sounds different. If I’m being invited to the table, it’s definitely going to feel different. This feels like an evolution of the original.

I’m warming to it, this some-seen utopian dream of employers of compassion – where family life is celebrated in all its nonconventional forms. One that’s flexible enough that we can all win at this parenting malarkey. We can all be the parents we want to be without the fear of losing out, losing time, losing our homes, losing our dignity.

Lourdes Walsh is a writer and designer.