Zara Oteng writes about the pain of family estrangement and the road to independence

On my wedding day in September 2018 I was the only member of my family present.

The day was a somewhat lavish affair, with friends, in-laws, aunts, uncles, nieces and godparents in full attendance. But for one of my sisters stopping by the church service unannounced, no-one else from my immediate family attended. For the rest of my wedding day, my mother, brother and two sisters were conspicuously in absentia.

Summer 2014 was the start of the schism between my mother and me. Periodic estrangement set in and we were on-again, off-again like old lovers until October 2017 when we spoke for the last time. Still, in my mind it wasn’t over until we finally tumbled into the abyss the following year. The familial bonds between my siblings and me followed soon after.

I’ve been asked so many times what went wrong. On the surface, what started as a nonsensical disagreement with my mother snowballed until my siblings felt they had to pick sides, and ultimately, they all decided not to come to my wedding. But if I were to try to explain what really happened, I would say that 2018 wasn’t the beginning of it all. If I were to sum it up, I would describe it as a death by a thousand cuts, as the accumulation of years of hurt and deep, roiling resentments. Some had begun small enough to go unnoticed for a time. Others I hadn’t even known existed. But what was clear was that we as adult children revolved around my mother in our own solar system. She was the biggest star and we orbited around her, like planets around the sun.

Stories like this are rarely ever the work of a single grievance. Blood ties aren’t the stuff that can be cleanly severed, all clinical and neat. Instead, they become undone over time in a slow, immutable process. Infractions, big and small, harsh words and cruel gestures loosen bonds until love ebbs away and you’re left with coldness in its place.

Some families are just like that.

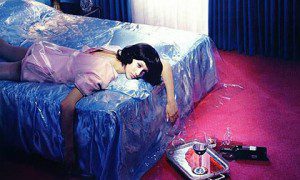

A biting sense of shame set in. I felt that people were looking at me as some kind of abomination. Often their eyes narrowed or their backs stiffened when they heard of the estrangement, and I couldn’t blame them. What kind of person is unloved by their entire family? What kind of twisted strangeness pushes a person away from their own herd?

I felt unprotected, exposed. I’d been in therapy for a while and kept going, week in, week out. I fell apart and then slowly began to piece myself back together. My husband was steadfast and gentle and by observing his family, I learned with awe that there is another way. Through conversations with his father, I found clarity and acceptance and my mother-in-law was also quietly supportive. She didn’t talk much, but I knew they were both in my corner.

A woman close to me told me to go where I am wanted. She offered me her arms and I sank into them time and time again. I borrowed her love, her daughters’ love in cupfuls. In many ways I was a child again, learning things for the first time; I hadn’t known that family could be like this.

I found out that I was carrying twins last September and although I was brimming with excitement, I was also terrified of perpetuating the same legacy of alienation that had made its way down to me through my mother and before her, my mother’s mother. And what if the things my family thought about me were true? That I was unworthy, fundamentally flawed, disrespectful, unkind. I so desperately wanted to be a good mother. “But you don’t even really know what a mother is,” my therapist pointed out.

Separating from one’s family of origin leaves an empty void that is impossible to fill. After losing mine, I unconsciously looked for replacements and for a time, found pretty good stand-ins. But appointing a friend – no matter how close – to become your sister or your surrogate mother comes with impossibly high expectations. After yet another disappointment, I realised with a start that no one can ever replace my mother, nor my sisters, nor my brother.

I was bereft once more, but I knew the rawness would lift. With the distance from my birth family, I stood a little taller, spoke a little louder. After a while I started to feel lighter. I slept better at night, and the recurrent nightmares I’d had since I was 17 stopped. Every now and then something triggers the hurt and it comes flooding back. There are still times when I feel that I don’t belong. But I no longer look at my friends or even complete strangers laughing with their loved ones, thinking that they possess something that I don’t. I look at my husband and my two children and I know that everything I ever really wanted I now have once again: a family to call my own.

Zara Oteng is a budding writer living in London with her husband and two children. You can find her at @zaraoteng on instagram and www.zaraoteng.com

Pass the Mic is a series where we hand the Mother Pukka platform over to other voices to share their perspective. Each piece is edited as lightly as possible and contributors are paid the going editorial rate.